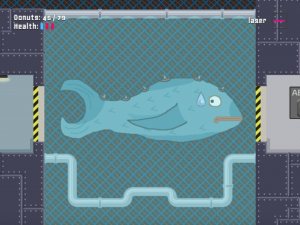

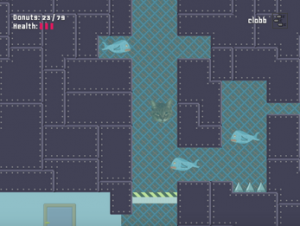

Hey everyone, we’re back with another sweet tale of student success! Today, we’re hearing from Damon Bolesta, and his experience creating his very first game – Donut Boy.

Hey everyone, we’re back with another sweet tale of student success! Today, we’re hearing from Damon Bolesta, and his experience creating his very first game – Donut Boy.

So Damon… tell us about the boy behind the donuts. How’d you get into game development?

I’ve always thought about developing a game ever since I was a kid, but it wasn’t until 2016 that I really made an effort to try and learn how to do it. I had been working as a web developer for a few years and had gotten some JavaScript programming experience under my belt, and I knew that HTML5/JavaScript games were becoming more popular, so one day I just Googled “javascript game engines”, and Phaser popped up a few times. I looked around for a few courses and the Zenva course was one of them, so I decided to work through it, and 2 years later, I had created my first game.

And now for the donuts behind the boy… You’ve got a pretty unique and quirky concept behind your game. Where’d you get your ideas?

The story of the game itself sort of just fell together. I knew I wanted a common collectable (like coins or rings), and donuts came to my mind pretty quickly. I then thought: “why would there be donuts scattered around everywhere?” Which obviously led me to conclude that there had been a catastrophic explosion at the local donut factory.

I used cropped images of actual faces as the players mainly because I didn’t know how to create animations at all when I first put them in (the game was actually called Face Game for most of development). A lot of individual game ideas came from either early games of my childhood, or just things in my life. For example, the idea to have a bubble weapon came from Milon’s Secret Castle for the NES, where your main weapon is bubbles. I was playing frisbee one day when realized that a frisbee could be a funny weapon.

It’s really cool to hear how something that started as a road block turned into a key aesthetic of your game! Tell us a little more about how you created the game assets – I saw that you used JavaScript, Phaser, and Photoshop, and even composed the music using Logic Pro X. What were your experiences using these tools and tech?

I had been using JavaScript for several years, but all of that knowledge was purely for creating website technologies. When I found Phaser, I was excited to use what I knew in a game-making context. I fell in love with it pretty quickly, and once I was familiar with the documentation and common techniques, I was able to implement singular ideas in just a day or two.

I had also been using Photoshop for quite a while, but never for creating pixel art. I’m not the best artist, so doing the art was probably the hardest and most time consuming part of making this game. In the beginning, I was sure I was going to either use pre-existing assets, or use single-colored tiles. But I’m really glad I decided to do it on my own, because I got a little better each day, and by the end of it, not only was my actual artistic ability a little better, but I knew how to create tilesets and spritesheets for animation.

I had been using Logic Pro X for many years to create little pieces of music, so I was very familiar with it already. One of my favorite parts of making this game was creating the music for it, so I hope that people enjoy the music!

It’s great to see how you brought all of those different tools together to create your game – and having heard the music, I think that it creates a great atmosphere for Donut Boy as he vanquishes all of his obstacles (seagulls, cats, and zombies…) in his mission to save the town. Did you have any obstacles that you needed to overcome in order to get the game up and running? And more importantly, how did you conquer them?

The biggest obstacle I had to overcome was definitely own lack of discipline. I started this game in February of 2016, and by the spring of that year, I had a nice little prototype put together. But I wasn’t positive what direction to take it in, and the flurry of ideas I had kept making development more and more intimidating. Realizing that some ideas would take possibly more than a year, and it wasn’t even guaranteed that the ideas would work, and I wasn’t even sure which of several ideas I wanted to work on… it basically killed my motivation to work on the game, and I soon stopped working on it completely.

As time went on, I started to forget how certain things were programmed, and how things were put together. I entered a really bad cycle of being intimidated to work on it, which made me not work on it, which made me forget more, which made it even more intimidating to work on it again. So I gave up on it. I had convinced myself that maybe game development wasn’t for me.

But one day in about October of that year, I decided that I had to finish what I had started, even if it turned out to be completely terrible. I forced myself to begin the agonizing three-week process of reviewing my code, relearning the fundamentals of Phaser, re-familiarizing myself with the documentation, and referencing back to Pedro’s videos to get me back to where I had left off.

This process was tremendously painful, but equally helpful. It was a good exercise in discipline, and through it I was able to develop a work habit that only got stronger over time, and that was crucial in helping me make consistent progress, and eventually complete my game.

Thanks for your honesty there, Damon – it’s great to remind people that struggling with game development and motivation is normal, but that it’s possible to get through it. You mentioned that re-familiarizing yourself with our courses played a role in keeping you on track. Could you tell us about which of our courses took you from rookie to patisserie-inspired platformer pro? How did they help you to create Donut Boy?

I took The Complete Mobile Game Development Course – Platinum Edition. It was great because each Module of the course has you complete a very simple game, each of a different genre. So not only did I learn about Phaser itself, but I learned about general programming tricks and techniques that are frequently used for a variety of different types of games. Different mechanics that I was familiar with from a players perspective, were shown from a programmer / designers perspective, which resulted in a lot of lightbulb moments for me.

I actually haven’t even completed all of the Modules – since I knew I wanted to create a platformer, by the time I had completed the first 7 Modules, I felt that I had learned what I needed to create the game I wanted. I was able to just continuously expand upon the groundwork that I created with the course and turn it into something that was uniquely mine. The Module format was really helpful in this respect, because I could learn exactly what I wanted without having to sit through the stuff I wasn’t as immediately interested in.

So now that you’ve fixed the Dough-Nutter 4000 and helped save the townsfolk from death-by-sugar coma, what’s next? Do you have any new games in the works?

I actually have already created a new game since I released this one only a month ago! I was so used to working on Donut Boy almost every day for the past few months that I felt a little lost without a project to work on. So I entered a Game Jam on itch.io (where Donut Boy is hosted) where the objective was to create a game in just 3 days.

I was feeling really well-practiced, so I took a stab at it and ended up creating a little game in one weekend. It’s called Final Flowers, and it ended up getting voted as the 4th most Fun game out of the 155 other games that were submitted to the Jam, so I felt really good about that.

I was feeling really well-practiced, so I took a stab at it and ended up creating a little game in one weekend. It’s called Final Flowers, and it ended up getting voted as the 4th most Fun game out of the 155 other games that were submitted to the Jam, so I felt really good about that.

It’s been great to hear all about you and the creation of Donut boy. Before we go, do you have any sage words of advice for other Zenva students who are having their first crack at game development?

I think there are two really important things people should keep in mind as they begin game development:

1) It’s Okay If Things Aren’t Done Perfectly

There were a lot of times where I wanted to implement something in my game, but I didn’t know the “right” way to do it. In the beginning, these were roadblocks to me. I didn’t want things to be hacked together, or done inefficiently, or the “wrong” way, so I would avoid doing them at all. But eventually, I decided that if I wanted to make progress, I would have to hack some things in whatever way I could. Sometimes it ended up being a good way to do it; sometimes I discovered a better way and was able to refactor the code down the line. I’m still positive there are fundamental components of my game that, if someone who was more experienced looked at it, would be insulted at the way I did it. But in the end, my code was causing the intended effect that I wanted in the game – and when you’re just starting out, that’s all that matters.

2) Anticipate Motivation Fading

I learned a lot about the relationship between motivation and discipline when making this game. When you’re feeling motivated – usually towards the beginning of a project – the work is easy. My motivation was fueling my work ethic so intensely that it felt like cheating. It wasn’t work at all, it was pure joy to be creating, learning, and watching something grow.

But at a certain point, that motivation will fade. It just will. It will go away, and the work won’t seem that fun anymore. It becomes work. It’s at that point when you have to incorporate discipline. You have to force yourself to work on it when you don’t want to. Especially when you realllly don’t want to. You have to create actual plans for yourself so that you have little goals to reach for. Make progress every day. Create a positive work routine for yourself. I had a system where, as soon as I was done my work for the day, I would take my fully-charged laptop to a coffee shop, and I would work on my game until my battery was at 5%. Sometimes I would make progress on my to do list. Sometimes I ended up working on something that I wasn’t planning on, even if that meant just plotting something new out in my head. Either way, I was making progress every day. It was through discipline that I was ultimately able to complete my first game.

In the end, the most important thing is that you can complete a project. One completed project is better than 100 incomplete ideas. So, start small, stick with it, and duct tape features together if you have to. You can do it!

And there you have it, folks! A huge thanks to you, Damon, for such a detailed and honest look into your development process.

Think that you’ve got what it takes to prevent the town from overdosing on sugar? Play Donut Boy here.

And if you feel like graduating from town hero to almighty saviour of planets, check out Damon’s latest game, Final Flowers.