NOTE: This tutorial is not updated to the latest Quintus version and doesn’t run with it.

HTML5 Mario-Style Platformer Series with Quintus:

- Part 1 – Create a HTML5 Mario-Style Platformer Game

- Part 2 – Adding Enemies to a HTML5 Mario-Style Platformer

- Part 3 – Adding Coins and Lives to the Mario-Style HTML5 Platformer

Are you a French speaker? If so, thanks to Alexandre Bianchi you can enjoy an adapted French version of this tutorial.

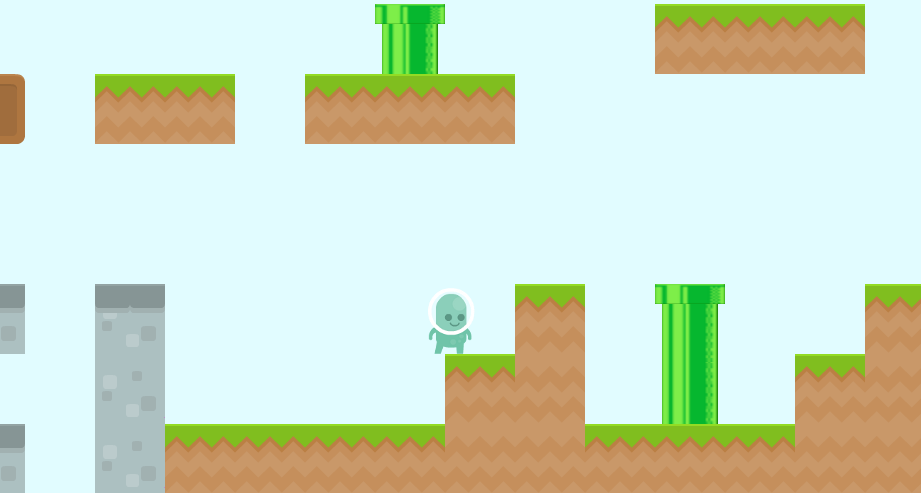

Among all game styles, platformers have stood out for decades and have proved to be a simply fun to play array of characters, blocks, tubes and monsters. In this tutorial we’ll create a simple Mario-style platformer using the Quintus HTML5 game framework, which allows you to speed up the construction of a simple and playable prototype.

This will be a three part series. In this first part, we’ll focus on constructing the level using the Tiled map editor, loading the level into the game and setting up the platform type of game (basically a character that runs and jumps around a scrollable level). In the second part of the series we’ll add enemies with different behaviours. The third tutorial will have coins and lives for the player.

The Requirements

We’ll be using the Quintus game development framework on this tutorial. This Open Source framework was created by Pascal Retig and is aimed for the creation of video games with JavaScript for mobile, desktop and beyond.

Starting points to get familiar with Quintus are the official guide, the G+ community and my previous Quintus tutorial.

- Familiarity with HTML, CSS, JavaScript and basic object oriented concepts.

- Clone or download Quintus from it’s Github page.

- Setup a local webserver. We need to run the code in this tutorial in a web server and not by just double clicking on the files. More on that later. WAMP for Windows, MAMP for Mac. On linux just type sudo apt-get install apache2.

- Download and install the Tiled game editor, available for Linux, Mac and Windows

- Have your favorite IDE ready (Netbeans, Eclipse, Sublime2, Notepad++, VIM, or any tool you use for coding).

- Download the source code here.

- Crack your knuckles and start coding!

The Setup

Create a new folder in your web server public folder (www folder in most cases), let’s call this new folder “zenvaplatformer”. In it, create the following sub-folders and empty files, and copy the JS files contained in Quintus/lib where shown:

zenvaplatformer/index.html

zenvaplatformer/data/

zenvaplatformer/lib/ —> copy the Quintus/lib JS files here

zenvaplatformer/images/

When working with Quintus, as well as other libraries from Github, it’s always good to keep an eye on the repo page as new features are constantly being added. You don’t wanna stay behind with an old version of the library. In the case of Quintus a lot of work is being done at the moment so keep an eye for new features and API changes!

After downloading the files from here. I’d recommend you do not look at the code unless you wanna ruin the fun of coding along. What you will need to do though is copy the game assets from /data and /images to their corresponding project folders.

The Map

All games, and in particular platformer games take place in a virtual world. In our case it’ll be a 2D, tile-based world. Tile-based means that the world is composed of individual “tiles” or blocks. Think of old NES games, how you could just find block patters that repeated themselves. Well that’s what we are building here too.

In order to create this 2D, tile-based world we’ll use the Tiled game editor. The Quintus engine has support for TMX file loading, which is one of the formats that can be produced by Tiled.

The map for this example is ready and waiting for you in the /data folder, but I still want to guide you through the process of a basic map creation:

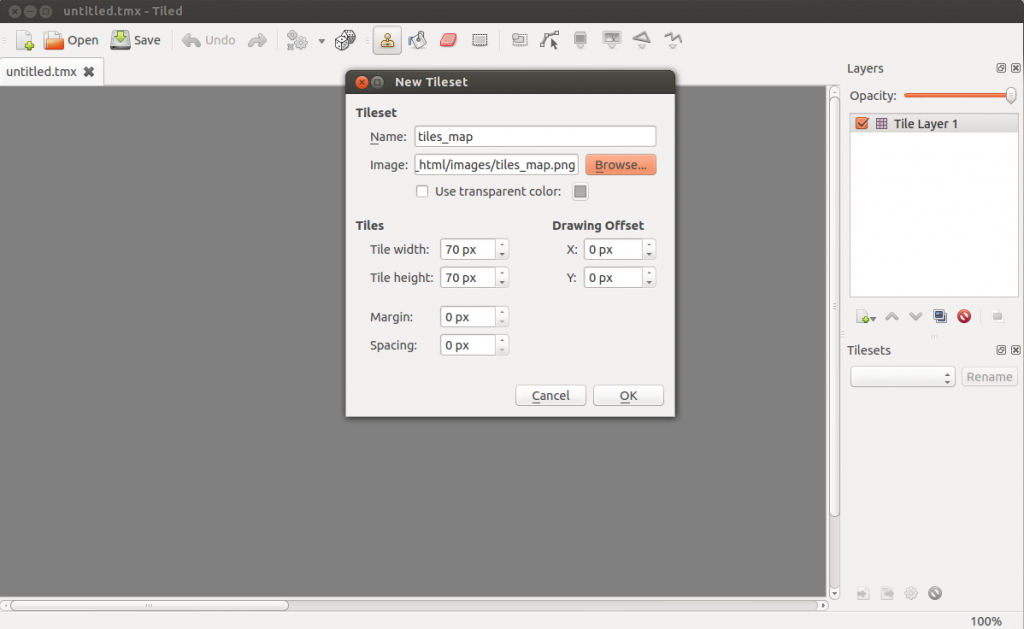

1. Open Tiled and create a new map. In the dialog box you have to specify the size of the map in terms of how many tiles or blocks it will have for width and height. You also specify here the size of the tile in pixels. In our example the width of the map is 40 tiles, the hight 10 tiles, and we’ll be working with tiles of 70×70 pixels.

2. Now where do we get the tiles from? we need what’s called a spritesheet or tileset, which is the name given to image files that contain all the tiles/sprites of the game. You can get plenty of free spritesheet at OpenGameArt.org, just read carefully the license of the images and give the author proper attribution in case they are Creative Commons. If they are Public Domain you can just use them without restriction.

But hey you just downloaded the example files so we do have a spritesheet to have a play with. Go to Map -> New Tile, then “Browse” and look for the file /images/tiles_map.png. Make sure you set the tile dimensions correctly (70×70), also there the margin, spacing and offsets should be 0.

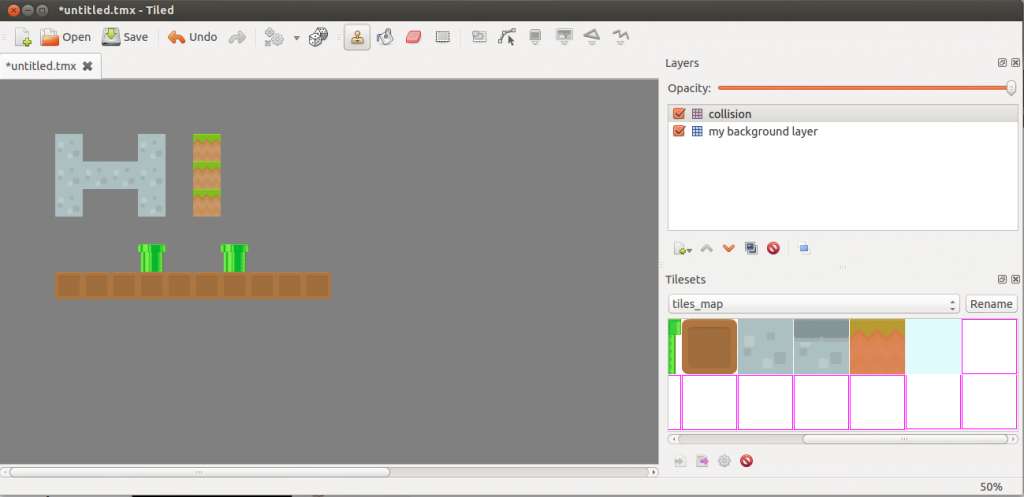

3. Having loaded the tileset we can now “paint” a map using the buttons on the menu. In the platformer example we’ll have two layers, one to hold the collision elements (the elements that will block the player’s path, or sustain him as a ground) and a background layer for just decoration. Create a new layer using the icon with the “+” under the layer’s area. Give them both names to distinguish them. NOW you can start painting your map.

4. If we want to have our files loaded with Quintus we need to save them in non-compressed XML format (tmx extension). Go to “Preferences”, then click on the “General” tab, where it says “Store tile layer data as” make sure XML is selected. Now you can save your map and this type of TMX maps are the ones you can use in your HTML5 games.

The Quintus Setup and Asset Loading

Copy the following contents to your index.html file:

var Q = Quintus()

.include("Sprites, Scenes, Input, 2D, Touch, UI")

.setup({

width: 960,

height: 640

}).controls().touch();

What we are doing here is basically setting up the Quintus object with the modules that we’ll use, activating the touch screen and platform controls. For a description of what each module does check out the official guide and also in my previous Quintus tutorial I’ve gone through the basics of the framework.

The next step is to load our game assets and to initiate and show our first level. An important concept in Quintus is that of “stages” which can be understood as “layers” that go on top of each other. Scenes are instructions that are “executed” in a stage. For example I have two stages (layers), I put one scene that loads the level in one stage and I put another scene that shows the game score in the other stage (that goes on top of the first one). In this example we’ll just have one stage which is where the level is loaded.

//load assets

Q.load("tiles_map.png, player.png, level1.tmx", function() {

Q.sheet("tiles","tiles_map.png", { tilew: 70, tileh: 70});

Q.stageScene("level1");

});

See how we load the images, then we create a sprite sheet for the tileset of the map. When you do so don’t forget to specify the dimensions of the tiles.

The Level

We’ve put on stage a scene called “level1”. We need now to initiate this scene. This is where we’ll load the game background and collision layers from the TMX file that came with the example (you could also load your own map here).

Q.scene("level1",function(stage) {

var background = new Q.TileLayer({ dataAsset: 'level1.tmx', layerIndex: 0, sheet: 'tiles', tileW: 70, tileH: 70, type: Q.SPRITE_NONE });

stage.insert(background);

stage.collisionLayer(new Q.TileLayer({ dataAsset: 'level1.tmx', layerIndex:1, sheet: 'tiles', tileW: 70, tileH: 70 }));

});

We are creating two Q.TileLayer objects here. One will be used for the background and one for the collision layer. See how we make reference to the TMX file and the layerIndex, which is the order of the layer in the Tiled map (you can also open the TMX file in a text editor to figure out which layer goes where). Important as well to make explicit the tile dimensions here.

For the background we are using type: Q.SPRITE_NONE which means it will be ignored by the player when it comes to collision detection. Collision and how it works is explained in depth in my previous Quintus tutorial.

You should be seeing part of the game map now in your browser.

The Player

The last bit we’ll be looking at in this first part of the tutorial series will be how to add the player and make it a “platformer” player. Firstly, we need to create a class for the player. Add the following after the Quintus initiation code:

Q.Sprite.extend("Player",{

init: function(p) {

this._super(p, { asset: "player.png", x: 110, y: 50, jumpSpeed: -380});

this.add('2d, platformerControls');

},

step: function(dt) {

if(Q.inputs['left'] && this.p.direction == 'right') {

this.p.flip = 'x';

}

if(Q.inputs['right'] && this.p.direction == 'left') {

this.p.flip = false;

}

}

});

Quintus has it’s own class and inheritance system and what we are doing here is creating a subclass of Q.Sprite called Q.Player. The constructor begins by running the parent’s constructor with some parameters: the player image file, the initial location (x,y) in the map, and jumpSpeed, which overrides the default jumpSpeed given by the component “platformerControls”, which is the concept I’m heading onto next.

Objects can have components added, which is basically adding a set of methods and properties. We are adding the 2d component, which provides basic physics (speed, acceleration, gravity) and collision detection. We are also adding the platformerControls component which makes the player movable with the keyboard (and touch screen as well since we run touch() when initiating the Q object.

The second method in Player, step(), is our door to the game loop. In most games there is something called a “game loop”, which refers to a set of instructions that are executed very often (many times per second) and allow the game to check for different states and modify variables accordingly.

All sprites in Quintus can have a step() method added. What we check here will be checked on the game loop. In our case we check the user input and flip our sprite accordingly, so that it faces the direction it walks to.

Time to Play

As you might have guessed, the last step towards having a player we can control is to actually place it in the level, for which we need to add the following in the scene initialisation:

var player = stage.insert(new Q.Player());

stage.add("viewport").follow(player,{x: true, y: true},{minX: 0, maxX: background.p.w, minY: 0, maxY: background.p.h});

The viewport will add a “camera” that will follow the player through the level as we are used to seeing. This camera will follow the player on x and y (the second parameter) and it will be restricted to the level area, so that we can’t show spaces outside of this level. You could restrict the camera to any area you want as long as you provide the coordinates in this optional parameter.

Righto, now we have a fully playable platformer demo. There are no enemies yet though, but don’t worry, that’s what we’ll be adding in the next tutorial in this series.

The Files

Download this tut’s source code here.

What Else to Check Out

At Zenva we have two high quality video courses on HTML5 game development that cover the entire process of making a game with HTML5.

- HTML5 Game Development for Beginners (Discounted for a limited time)

- Create a HTML5 Game from Scratch (Discounted for a limited time)